Joan Vaccaro BSc PhD FInstP MAIP

This is my personal home page where I outline my professional career and interests, as well as explain some more personal topics.

The beginning

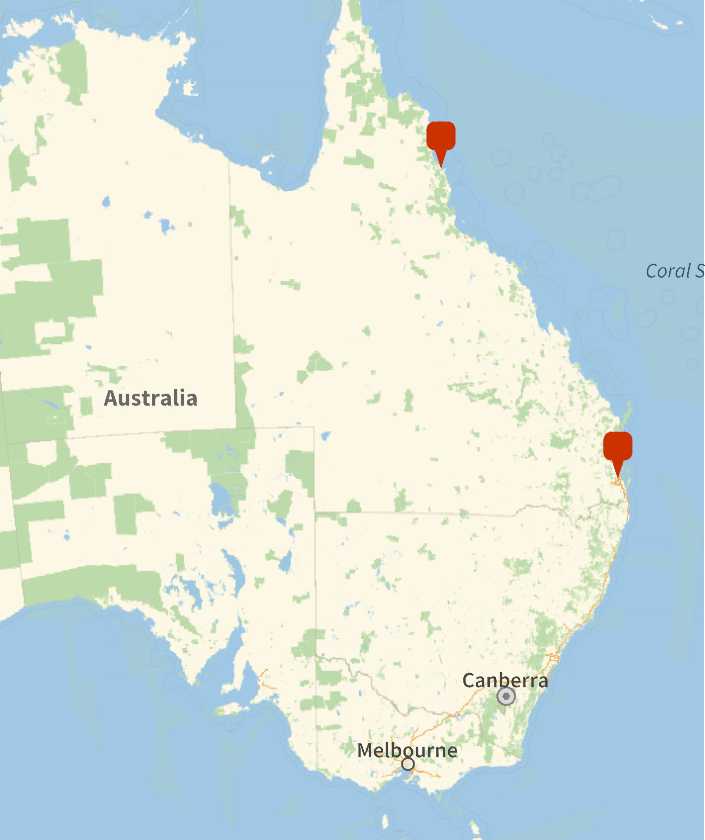

I grew up in the 1960's in El Arish, a small town in north Queensland with a population of about 650. The town lies in a farming community that is dominated by sugar cane and includes banana and tea plantations, and some cattle properties. My parents were both born in the surrounding region from Italian and Maltese migrants. They had attended school up to grade 5 (mother) and 7 (father), and naturally favoured the familiar, practical things in life. I learnt many skills from both of them under their guidance, but also just by observing them. My mother had taught herself to sew. She had oodles of reels of threads of different kinds, colours and gauges, and different fabrics of various weaves—some stretch—and various threads—some cotton, others a mix of natural and synthetic thread, and some patterned, others plain, and so on. Her second sewing machine (a Bernina) was an intricate mechanical device with internal rotating cams that controlled the shape of stitches. It called for investigation and drew me in. I learnt to sew by trial and lots of error on scrap pieces of fabric. Occasionally, she did her own woodwork and painting when my father "took too long to get around to it". She was inspirational, saying to herself "if they, or he, can do it, so can I". She showed me that ability was not limited to circumstance and privilege, it was available for development simply by desire. I also listened to my father talk about his work as a motor mechanic, and learnt about mechanical things, and how he solved mechanical problems step by step, narrowing down the possibilities. I watched him use tools and automatically used them in the same way (such as clasping pliers between thumb and forefinger and using the little finger to separate the jaws). Keenly watching was as important as listening. He once owned a mechanical repair business in partnership with his brother. When that folded due to cash flow problems associated with farmers being able to pay only when their crops came in, much of the equipment was moved into a workshop at home. I had full access to hand saws (wood and metal), power drills (drill press and hand drill), a 3-phase grinder, hammers, assortments of screwdrivers and pliers, an assortment of spanners (open and ring) and sockets for SAE and Whitworth threads, paints and solvents, sand papers, files and rasps, wood chisels and planes (Jack plane and spokeshave), cold chisels, metal fixings (bolts, screws, and nails), a set of taps and dies, a big wooden bench with an engineers vice fitted to it, measuring instruments (rules, a micrometer, vernier gauge), a stock of timber, and so on. It was another of my playgrounds, although at times, a somewhat dangerous one.

My old home in El Arish (photo taken 2015)

I was naturally curious and looked for meaning and explanations. I think this was spurred by the fact that people gave explanations in general conversation implying that logical reasoning underlay everything. Initially this led to inappropriate extrapolations. For example, at some point my father had explained that our black (Bakelite) telephone transformed the sound of our voices into electricity which ran through the black wires connected to it to another telephone, and so on. Once, when I was perhaps 4 or 5 years old, I was under our little house playing in the 60cm void between the floor and the dirt, as I often did, bumping my head painfully on the floor bearers in the process. I had discovered that the electricity mains wiring ran along a bearer under the floor on the east side of the house. Interestingly, there was also a junction box at one point in a long length of wire. Strangely, the junction box looked like a regular light switch with the toggle lever missing, leaving a circular hole. Perhaps an electrician had improvised the switch casing as a junction box. I didn't know that at the time, of course, but I did know I shouldn't poke my finger in the hole because electricity was very dangerous. It occurred to me that I could speak into that hole, and my voice would be carried by the electricity in the wires to my mother who was above me sewing using her Singer sewing machine, which was connected to the electric wires. I began speaking to her through that hole. I had to raise my voice to get her attention. Eventually I was shouting. We had, what I found to be a difficult conversation, where she didn't understand that I was using a telephone and appeared annoyed at all my shouting. Clearly, the explanation or my understanding of the telephone principle was incomplete. Perhaps explanations are not necessarily transitive. I persisted, nevertheless. Eventually something as simple as washing the dishes would lead me to the question, how can a towel dry a wet dish when the towel becomes wet immediately it touches the dish, and a wet towel cannot dry anything? The towel seemed to be just sharing the water, not really drying. The concept of a spiritual soul that parents and relatives talked about was very intriguing. My mind was supposedly a spiritual thing. But more concretely, the phrase "I thought of something" would lead me to investigate what a thought was. I tried to watch myself mentally have a thought. Can a thought be of itself? Despite the thought always slipping away jumbled up somehow, I persisted. In fact, I still watch myself thinking, now more for checking for consistency from another perspective, and for how I'm arriving at conclusions and do problem solving.

I started grade 1 at El Arish State School in 1962. The school was a 15 minute walk from home. I think my first teacher was Miss Borsarto. We learnt spelling and arithmetic using stone slates in the traditional post-neolithic manner of the day. We read stories of Dick and Dora, and the house with red geraniums growing out of a boot that was mistaken for flames of a fire! We cut shapes and folded small pieces of coloured paper. It was fun. A somewhat grumpy Mr McNiel was the headmaster, but thankfully he didn't teach me. However I was taught by Mr Jenkins who could be rather grumpy at times. Once, in grade 3 I think, I had tried to set alight to some card at home but, for some unknown reason, it only smouldered. So, naturally, I doused it in petrol that we used for the lawn mower. "That'll do more than smoulder", I thought. Unfortunately, my right hand was also covered in petrol when I lit up the card with a match, and it also burst in flames. Instinctively I shook my hand vigorously, but that only made the flames fan out as they followed the movement with a pulsating, whooshing sound. Simultaneously, I began running and yelling an elongated "Arrr...". The running, whooshing, and yelling continued from the back of the house where my mischief had started, around the side past the water tank, and to the front yard where I noticed that the whooshing sound had stopped. I was no longer on fire. I was still scared though, and anxious for my tingling hand. Mum appeared, and a visit to the ambulance in Silkwood quickly followed. The good thing that came of the incident was that I had a valid excuse for not doing homework for a few weeks while my writing hand was bandaged up. And I did exactly that, nothing. The downside was that when the bandages came off I remember Mr Jenkins tugging painfully on my ear for not doing well in a test saying, "you could have still learnt your spelling—you don't need your writing hand for that!"

Eventually Mr Coomber replaced Mr McNiel as headmaster, Mr Jenkins left and I moved into Mr Coomber's classes. He was an inspiring teacher. He encouraged us to keep going to school after the school leaving age of 15, and to learn as much as we could. His encouragement has resurfaced many times in my life.

Among my school friends were Stephen Garside and David Faulks. They were as adventurous as Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, escaping school and usually hiding in a cave in a bend of Flynn Creek on the south edge of El Arish. They knew how to survive. We'd only have rumours to go on while they were away, and we'd get only part of the story when they returned to school. What did they do for light, warmth, and food? There were stories of cigarettes, stashes of soft drinks and lollies and so on. Once they left El Arish and headed south for Townsville, hitch hiking their way. They were gone for a week that time, I think. There was a police alert. I never found out why they would leave, whether there was a significant problem that drove them to it. Their friendship and mutual support must have been strong. It just seemed to be the most adventurous thing a kid could do, and I admired them for it. They gave me reason to see life as an adventure.

Stephen and David lived to the south east of me. Alison Crisp, Cathy Crighton and Glenis Malloy lived on the town block just north of where I lived. Alison's family owned a sawmill across the road from where they lived. It was a busy place, with machinery whirring away, great logs with bruised bark in stacks, cranes with chains moving about stirring mud and swashing pot holes when it rained, and a giant pile of sawdust at the far northern point on the edge of the scrub. It was a ply mill as well and the veneers of plywood would be stacked vertically in bays to dry before being glued. The mill was always worth a look, and take in the smell of freshly sawn timber mixed with the odours of oil and sulphurous mud. Once my cousin, John (or Charlie? - I was around 4 years old I guess) de Brincat, who lived in the same street as Alison, invited me to help build a cubby house using scrap ply veneer from the mill. The ides was to use a couple of wooden carpenter horses as the frame on which the veneer was tacked. It was rather slap happy, but spectacular nonetheless. Looking from the inside, the sunlight would diffuse through the veneer highlighting the grain the pattern of swirls around knots.

Henry Hampson, who was gifted at drawing, lived in the block to the east of me. His big brother played cricket at some advanced level. There was also Neil Williams, who was very clever and wanted to be a sugar chemist. He lived on a farm somewhere. I recall many chats together. Once I bought a cupcake quantity of lead from him as ballast for a sailing boat I had built. Neil had sourced the lead from obsolete lead-acid batteries, melted it and poured it into the recesses of a cupcake tray. I found I could shape the lead using a spokeshave, and screwed it to the bottom of the keel.

The nearest high school was in Tully, and so going to grade 8 meant taking the school bus, driven by Mr Faithful, every day. High school seemed like a city. There were hundreds of students from parts the surrounding areas that I didn't know. It was a busy place. I don't recall any bullying, although there was teasing and very occasionally there was a fight. I enjoyed going to school. I think my science teacher was Mr. Wilson. The science laboratory was full of wonderful equipment—even a Wimhurst machine!—chemicals, glassware, and interesting smells. I loved any lesson in it. I will never forget that basic chemistry experiment of mixing hydrochloric acid and a solution of sodium hydroxide until the litmus paper changed colour, and then evaporating the liquid using a Bunsen burner to find a residue of salt—just table salt—that you could taste. The ordinary world in which table salt was a part suddenly had a deeper side to it. The veil of simplicity that accompanied the ordinariness of the world lifted slightly hinting at so much more to understand.

There was a time when students were allowed to go into the laboratory—unsupervised, mind you—during the lunch break. My friends, Neil Williams and Leo Pensini, and I would try using some of the equipment. We used the Wimhurst machine of course, but I don't recall being able to generate sparks. Tully, being one of the wettest towns in Australia, had a humid climate and perhaps this limited the size of the stored charge. The professional microscope was fun. Somehow we managed to get a tiny drop of liquid mercury onto a glass slide and observe it under the microscope. Despite the almost invisible size of the drop, we could see a distorted view of the room reflected in its magnified image. A waving hand was clearly visible. This view of the microcosm was both extraordinary and yet somehow expected. But just imagine if we had observed a small enough drop to see evidence of the wave nature of light! That would have been puzzling. Of course, there were other students, with less curiosity, who would fool around. Eventually, the sexually suggestive poses of the human skeleton they arranged on view for the next laboratory class wore down the patience of the teachers, and the open access to the laboratory was rescinded. Nevertheless, the teachers were good, in general. I remember the encouragement of Mr Turner, my English teacher, to embrace the changing times in the late 1960's, and engaging with the unfolding social revolution in lifestyles and forms of expression such as music.He once told fellow student Peter Devon in grade 10 that he could use his long golden hair more expressively, "throw it about a bit" (and I wished I could too, but my hair tended to curl up).

A photo of Ralph Nissen's electrician workshop in Wilson Street, El Arish. Reproduced from Odin's Beach, David and Noela Nissen, Mission Beach Historical Society, 2022

I will never forget the atmosphere of technological progress and scientific achievements. I viewed the moon landing of 1969 as pointing towards ever-more intriguing developments in the future. I loved learning about science. I received a microscope for a birthday when I was around 10 years old. Biology of the miniature was just fascinating. I was thrilled to receive a crystal radio kit as another birthday gift. Magnets, clockwork mechanisms, batteries, torches (flashlights), electrical wire, electric motors and the like were available, not only to be to be explored for their own sake, and but also to be used as elements in constructing something more complex. Wood could be sawn, chiselled, planed, nailed, screwed, and painted to make "things". For example, after been shown once how to do it, I cut out and shaped wooden propellers, and made wind mills with them that would spin wildly in the wind. I built a wooden light-box projector from a design in a book using the lens from a magnifying glass and sheet metal from empty food cans fashioned and soldered into a telescopic focusing barrel. Lighting was provided by two 60W incandescent bulbs in lamp holders—bought with pocket money from the electrician Ralph Nissen (see photo)—that I wired to take the 240VAC supply with Dad's help. It projected photos onto the wall, but the bulbs would make the box quite hot over time. Books in the library at Tully State High School contained many treasures about that larger world that surrounded us. They contained ideas about how things worked, what people had done, how discoveries were made. They seemed to beckon me to try to do the same, and fuelled my imagination. One book, "Secrets of Chemistry" by Robert Brent (Paul Hamlyn, 1965), explained how to set up a home laboratory. I eagerly gathered household and gardening chemicals, bottles, tins, home-made spirit lamp, home-made balance, used laboratory equipment (test tubes, rubber tubing) and some sample chemicals (magnesium ribbon, litmus paper) generously gifted by the school with the help of a science teacher, and set about discovering the world of chemistry for myself.

This was the perspective from which I viewed the world while still living in El Arish at about 16 years of age, and wondering what future it held for me. In secret I dared to hope, but without any real expectation of being anything more than a spectator. There were personal challenges, cultural and religious conflicts, along with rural working-class naivety that seemed to rule out any optimism. Growing up is not easy for anyone. (Nevertheless, I did survive, and looking back I think the reality has panned out to be better than anything I had hoped for, many times over!)

Turbulence

My parents were worried about the relatively scarce career opportunities on offer for their seven children in the local district around El Arish. This led them to make the rather momentous decision in 1972 to move the family to Cairns, a growing tropical city of 30,000 people that was 120 kilometres further north. Going from the state-government run schools in El Arish and Tully to the private Catholic school, St Agustine's College, in Cairns was a significant event. Whereas the general attitude in the government schools was non-sectarian and egalitarian, I found the general outlook at St Agustine's to be one of privilege and status, which has always felt not quite right. Being a private school, St Agustine's charged enrolment fees which appeared to carry with it a need to show it had some distinction over other non-fee schools. This seems to infiltrate the general ethos of the school and it also aligns with the air of superiority that accompanies the religious viewpoint. Indeed, it aimed to be the best in the area, and perhaps it was.

Being the best was not so important to me. I had begged my parents to let me attend one of the regular, co-educational government schools in Cairns for what I perceived to be an education in a normal social environment. I did not need the protection of, nor wanted to be in a quarantined community. I didn't mind the challenge of finding my way in the diverse community that inhabited government schools because it was a sample of the wider community that I would deal with for the rest of my life anyway. But my parents insisted that I attend a Catholic school because they had pledged when they married to send their children to one whenever it was practical, and now it was. At the time, I resigned myself to accepting their decision rather than take any alternative choice, because I wanted to go to school most of all and it was to be only for my final 2 years of schooling. It was with great reluctance, therefore, that I entered the school, and that may have made me more sensitive to the differences it represented.

Despite my initial misgivings, however, I did make some good friendships that I still cherish today, and I remain impressed with the teaching and the facilities at the school. I learnt many new concepts and skills that remain rooted to memories made there, and so the school remains important to me. I was awarded the physics prize in grade 11, jointly with Robert Wenzel I recall, which was rather a surprise to me. I did love the topic (along with mathematics, chemistry and economics). Nevertheless, I rebelled somewhat against the regime of authority in a way that was out of character for me compared to my behaviour as a conforming student at my previous schools. In my defence (if it is needed) I hadn't previously experienced social and ideological constraints of the kind that was the baseline at St Agustine's. The extremely short hair ("short back and sides") policy at St Agustine's ensured that students could not identify, or participate socially, as a typical youth of the day for whom hair styles were part of one's personal expression contrasted markedly with the attitude at Tully State High. At St Agustine's we were to appear quite distinct and apart from everyone else. I was once suspended for a short time and threatened with expulsion. It was about this time that I discovered that wondrous altered mental state induced by cannabis. I also experienced what being really quite drunk is like at a wedding (Aunty Margie and Uncle Dom) in Innisfail. At the same time, my Christian religious beliefs waned as my curiosity drove me to explore other possible viewpoints. My world was clearly opening up! However, I found people, social situations, and my place in it all ever more complex and challenging, and ever less clear.

Feelings of not being valued and not belonging, which are not unusual when growing up, unfortunately became more common. When I eventually mentioned suicide ideation to my mother I quickly ended up in front of the psychiatrist, Dr McGovern. After finding drug therapy didn't work so well, I was given a course of electroconvulsive therapy. It's quite a scary thing to think about subjecting oneself to. This occurred someway through grade 12. I didn't attend school for the second half of the year. Friends from school (Michael Gillman, Stefan Michalov?, and others) visited me during a relatively long stay in hospital, which was very welcome. But my general recollection of that time is sketchy and distorted. There are even incoherent threads that threaten to form into a memory of an unlikely tragic story involving a violent crime, being a fugitive, and living in a cave on a beach in torrential rain!

Eventually I recovered some composure, sufficient to celebrate the end of year 12—and school—with friends and, of course, alcohol. I presume some kind staff at the school advocated compassionate consideration on my behalf because I was awarded my senior certificate despite missing my last semester which accounted for a quarter of the course. I am very thankful that they did. I was 17 years old and still recovering. I decided to take a gap year before going to university. My intention was to find my bearing while enjoying new freedoms and venturing into the world at large. Fortunately I landed a job as a clerical assistant in a semi-government firm, the now defunct Cairns Regional Electricity Board (known as CREB). I had lunches in a nearby cafe (Sally's) where I met young people living as hippies. I had been intrigued with the hippy movement for some years and eagerly wished to join. I left home and moved into shared living with some—a guy and two girls, names forgotten—in Holmes Street in the suburb Stratford. That led to more hippy friends—Tom and girlfriend Sheryl, Tom's sister, Mick, Ricky (the Mahjong player), Fiona, the philosophical guy with cool John Lennon circular glasses, and others—and after only a month or so I left my job, and moved house again landing in 123 Sheridan Street in central Cairns. I recall lots of colourful, embroidered cheesecloth clothes, incense burning, candles, and music. Hand-painted murals of leafy vines and flowers were common. The scene was "cool, man" because things were so "far-out", although "Fuck man, some things were just not cool. Heavy man!". We referred to ourselves as "freaks", and others as "straights"! At that time, Kuranda, a small town north of Cairns, had become a mecca for hippies, and some had cobbled together unused building materials, often removed illegally from anywhere it was found, into squatter shelters in the surrounding virgin rain forest. I stayed, or squattered, for a time in one that was reached by walking through the dense forest without following any marked pathway. You needed to be shown where it was. Living there was a sample of an ideal form of escapism, and the damp, mildew, spiders and ants made it even more basic, and therefore cool!

However, more turbulence soon followed, including a drug overdose (Parnate), a brush with the law involving jail time in Etna Creek (where I met Kurt who wanted to buy or lease an island and build a commune), a Mohawk haircut, and it culminated in a 3 month stay in a psychiatric hospital (The Prince Charles) in Brisbane where I made new friends: Peter Booker, Howard Fryberg, wonderful Debbie from Petrie, lovely June, another Tom from Woodridge, the cool guy with a beard and limp and Jethro Tull and Santana fan, and others. Fortunately, the therapy was less invasive and I learnt to re-establish my bearing in a more measured way. Returning to Cairns, I landed work doing manual labour, and made new friends, and solidified my outlook on life. Kurt appeared in Cairns one day inviting me to join him and his brothers and friends on financing and building the island commune. He was serious, and the offer was tempting. But I was being dragged back by circumstances into a more conventional lifestyle (becoming a "straight"), and I declined. It was about that time that I met David Ahern who became a lifelong friend. There were all night pot parties and occasionally some pills (Mogadon). At the gap year's end, I enrolled, as planned, in a bachelor degree in psychology (with as many electives as I could in physics) at the University of Queensland, but I lasted only 4 weeks due to a lack of preparation (what was that stuff that I had learnt in school?) and getting lost in what seemed to me to be the complexities of student life (what was an "undergraduate" and was I a "postgraduate" having finished grade 12?).

Calm weather

I again returned home to Cairns and reconnected with my family. My cousin Joe introduced me to a labouring job at a road constructing firm working with him. It was a new sphere of the world to explore. This was a period of steady work and an introduction to his social group. I met Gabrielle who became the love of my life. She gave me a pivot point on which I could build long term dreams while continuing to explore this strange world we found ourselves in. Meanwhile I had pared away my religious beliefs until, in one moment of realisation at age 19 years, I made the conceptual jump to accept, and begin to consider seriously, the atheist perspective.

Motorcycles came next. David's younger brother Robert bought the first road bike, a Yamaha TX500. Next David bought a Kawasaki 400, and I followed with another Yamaha TX500, bought from my old school chum, Ken Harris. Those times were fun. Cannabis was regularly available and sometimes magic mushrooms too.

My curiosity continued. I found the book "Relativity: The Special and General Theory" by Albert Einstein in the local Cairns library. It was written in 1916 for a general audience. Einstein said that time and space were not how we think they are. In particular, if a person travels very fast their clock will run slower than a clock left behind. This means time is not the same for everyone. The lengths of things was also different. I found this amazing. I wanted to know more. But my curiosity wasn’t just about physics. I was also puzzled about what it means to be human. I wanted to understand who we are, how we think, and where we fit in the scheme of things. I wanted to know how to think about consciousness and free will. I found another book by the philosopher Herbert Spencer called "First Principles" written in 1867. I suspected that physics, and science generally, would help me understand it better. Then I read "Physics and Philosophy" by James Jeans (1942). He talked about a substratum were Nature operates in a strange quantum way. Free will lost its meaning and was replaced by the principle of determinism, that all physical changes could be explained through physics, in principle. I now saw free will as an illusion.

Microcomputers appeared on the market. Gabrielle and I bought a Tandy TRS80 and learnt to program in BASIC. Computers started to appear in workplaces. Feeling I was going to be left behind as this new technology gained momentum, I looked for career opportunities. I considered training in computers as a default position that I hoped I could fall back on, but with a secret wish that I could do something in physics. That was my frame of mind when I enrolled in a bachelor of science degree at Griffith University in 1981 at age 24 years.

Academia

Undergraduate learning was blissful. In my naivety, I had in mind to check everything that was taught in physics to see if I could find something overlooked. However, I soon found the material too well developed and at a well-trodden foundational level to offer me any such opportunities. Where the strength of the argument did appear to wane, it was only to make some conceptual connection to more developed theory that was beyond the scope of the level being discussed.

Some highlights of first year were learning the basics of chemistry (chemical bonding, solubility and buffer solutions, thermochemistry) and biology (the ATP energy cycle, gene splicing, DNA, RNA, mtDNA, ...) that has been very useful throughout life. Maths was wonderful, particularly convergence and the limits of sequences, and then calculus, probability, complex numbers, linear algebra! Such powerful ideas with far reaching implications. In physics there was mechanics, electricity and magnetism, and optics as expected, but also the very exotic special relativity and quantum mechanics. The historical justification for relativity and quantum mechanics has had a lasting impact. The manner in which Einstein selected two principles (speed of light being constant, laws being the same in all inertial reference frames) on which to formulate special relativity, and in doing so discard Galilean relativity, is simply profound. I wondered how this could be repeated. How does one get to be in a position of being confronted with ambiguous physical concepts, in which the possible resolution is a coherent subset? The lesson for me was clear: be always on the lookout for a comparable situation in the future. So rather than find something overlooked in my course material, I had learnt to be alert for a special kind of situation. I knew that any such situation would likely arise quite rarely in physics, perhaps no more often than once a century or so, and that I may not be sufficiently gifted to recognise it or do it justice. Nevertheless, the lesson forever changed my way of thinking about physics.

Although the development of quantum mechanics was equally as profound, the lesson it provided for me was less clear owing to being more incremental, with contributions from Planck, Einstein, Bohr, de Broglie before the final steps by Schrodinger and Heisenberg. What was clear, though, is that one must try anything in order to solve an anomaly. That too is indelibly impressed upon me, but it is also not so unexpected.

There was also a stream of teaching in first year called Science, Technology and Society that I enjoyed. Assessment involved writing essays, which had been the bane of my life at high school, but the enticing nature of the topics more than compensated for that, and Gabrielle helped with editing (what an angel!). The courses were philosophically based—which automatically ticked a box for me—and sought to understand science from its historical perspective, see how it was distinct from other human knowledge-based activities, and explore its relationship with technology and society in general. The teaching stream naturally lent it self to developing report writing skills, which was also part of its objectives. We learnt about the ancient Greeks, the impact of the Church and Christianity on learning, Tycho Brahe, Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo Galilei, Newton and so on. I found the Copernican Revolution profound: that upheaval of perspective forced by empirical investigation and rational thinking. How easy it would have been to dismiss the new perspective of a sun-centred cosmos, and continue with the more familiar Ptolemaic view of an earth centred one, after all, would humans not occupy the "centre stage". And how obvious it seems to us today, growing up with with the new perspective firmly embedded in our way of thinking. In fact, the ease at which we now discard the earth-centred view is a key point of the lesson here. I needed to be alert for a situation where a new perspective is needed that challenges our most fundamental notions, and where that perspective may become almost self-evident to later generations. The extent of the challenge, therefore, should not limit the scope of the new perspective. I wondered if I could rise to this kind of situation, or if I would be trapped, snared by cherished beliefs as I imagine many of Galileo's contemporaries were, and slumber on. I hoped that my escape from the religious beliefs of my upbringing while knowing how others in my family remained bound was good preparation for avoiding an analogous "earth-centred" trap in physics.

In any case, I could not have wanted a better first year experience!

Places I've lived

17580